In the very first episode, Ernie Allen, the former head of the U.S.’s National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, tries to shed some light on why this particular case captured the public interest to such a ferocious extent. It was the particular circumstances, he explains—the middle-class parents on holiday, the irrationally nightmarish scenario of a child being abducted from her bed right under their noses. Far from judging the McCanns for leaving their children unsupervised, many parents at the time empathized. And Kate and Gerry, one journalist explains, were “very attractive from a news editor’s point of view.” As doctors from working-class backgrounds, they were symbols of British aspiration—a story that readers loved to buy into.

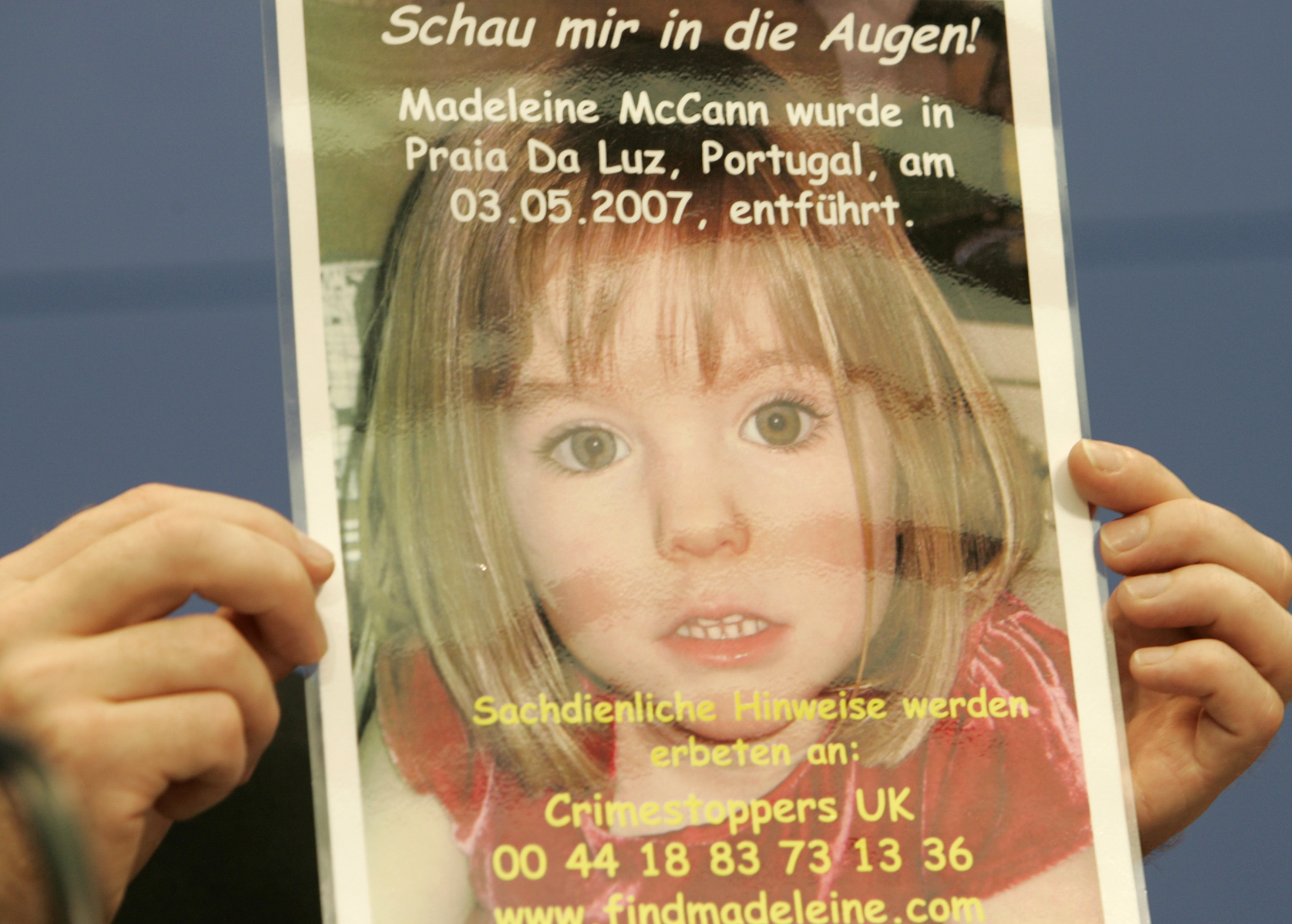

But there was also Madeleine herself. She was white. She was blonde. She was impossibly adorable in the images that soon tattooed themselves on the public consciousness: grin-grimacing with toddler enthusiasm in a furry pink tiara, standing shyly in her Everton shirt. The reality of missing-white-woman syndrome is that the media have long been disproportionately fascinated by crime stories featuring white women, while neglecting stories about women of color. In Madeleine’s case, the phenomenon was only amplified by her childhood and her vulnerability. As the series explores in episode 3, the Portuguese media soon began to chafe at the focus on Madeleine over other missing children in the country at the time. The more the McCanns used the media to publicize Madeleine’s disappearance, the greater the resentment became.

None of this, the series makes clear, is to say that the resources invested in finding Madeleine shouldn’t have been spent. And while the show is investing yet more time and energy in exploring Madeleine’s story, Cooper said she hopes it can also draw attention to the children who disappear and aren’t looked for. In one of the later episodes, Cooper and Smith interview a Spanish private detective hired by a benefactor to investigate Madeleine’s disappearance, who mentions how unusual it would be for a middle-class child to be targeted by a kidnapper. “They usually go after lower-class kids, kids from third-world countries,” he says. If they took Madeleine, he says, it’s because her value would have been “really high.”

This statement is disturbing for multiple reasons. On the one hand, it spells out what most people would prefer never to think about—the fact that children are bought and sold every day. On the other, it gets at the fundamental dynamics of why Madeleine’s disappearance became such an all-encompassing story, compared with other missing children: the perceived value of different lives, and the empathy gap in individuals between people who look like them and people who don’t. The distance between children the readers of The Sun and the Mirror could easily liken to their own offspring, and children they couldn’t.

The detective’s remarks also highlight another reality about Madeleine’s case—the value she represented for people who soon saw how they could profit from her disappearance. Gonçalo Amaral, who was removed from her case in disgrace after criticizing the British police and the McCanns in an interview, reportedly made £350,000 by publishing a book, The Truth of the Lie, in which he wrote that Madeleine’s parents accidentally killed her and hid her body. One of the American private detectives hired to investigate Madeleine’s disappearance, the series details, turned out to be a con man.

But the institution that profited the most, and the one that’s never really been held to account for how wildly it behaved during that period, is the tabloid press. There were headlines insinuating that the McCanns killed Madeleine, that they burned her body, that they threw her into the sea. Smith and Cooper interview Kelvin MacKenzie, the former editor of The Sun, who blithely details the rules that tabloids live by. “In our world, if there’s a question … it becomes a fact,” he says. “The answer doesn’t matter, right?” National newspapers, in that moment, were all facing off against one another to sell copies to readers who wanted to know what happened to Madeleine, and the only thing that mattered to them was spinning the most enticing story.

“The McCann case,” Brian Cathcart argued in the New Statesman in 2008, “was the greatest scandal in [British] news media in at least a decade.” Even though Madeleine’s disappearance predated social media, it predicted some of the worst excesses that Twitter and Facebook would go on to enable: rampant misinformation, distortion of the facts, the virality of certain news stories. You can debate, as people certainly will, whether it’s appropriate to build a television series around a child who’s never been found, and whether the impulse to revisit the case is distinct from the feverish cultural fascination with Madeleine in 2007. To watch the series in its entirety, though, is to see in sharp, damning, and exhaustive detail all the ways in which a family’s nightmare was transformed and served up for consumption as a public spectacle.

Prošlo je gotovo dvanaest godina otkako je svijet šokirala vijest o nezabilježenoj otmici u portugalskom turističkom resortu.

Trogodišnja britanska djevojčica Madeleine McCann oteta je iz resorta dok se igrala na igralištu u Praia de Luz, a počinitelji tog gnjusnog zločina, kao ni oteto dijete, nikada nisu pronađeni. Njeni roditelji večerali su u restoranu kompleksa, a Maddie je mirno spavala s dvojicom rođaka. Potom kao da je nestala s lica Zemlje.

Otkrit će nove informacije?

Priča o trogodišnjakinji postala je broj jedan u svijetu. njezin lik tiskan je na stotinama tisuća majica, u novinama, na pakiranjima prehrambenih proizvoda, plakatima... Gotovo da nema svjetske informativne emisije, novina, radija ili web portala, koji nije do u detalje pratio sve što se događalo oko "m...

Za sudjelovanje u komentarima je potrebna prijava, odnosno registracija ako još nemaš korisnički profil....